If you look at any desk that I use, you might not think that I have an ordered mind. It can be a little scary, I admit. I am of the opinion, however, that I’m capable of imposing order on certain parts of my mind – especially when there’s a show to be done. This is important, because I think that really pulling off a show requires some kind of plan. It doesn’t have to be written out in detail, but it has to exist in some form. You can’t just throw things together at random and expect them to work. A clear idea of what’s truly important is a really helpful sort of thing.

It did strike me one day that it might be interesting to attempt putting my basic, mental plan down in writing.

So, here you go.

The Pre-Game

Early Is The New On-Time

My general philosophy is that, if you’re early enough, you remove the need to worry about “the critical path.” The critical path is the shortest sequence of tasks necessary to complete a project successfully. Our project is the show, and the critical path for the show is the minimum necessary to survive the night.

Sometimes, that’s all you can do – but do you really want the bare minimum to be your best practice?

Nah.

The critical path for the show might be two vocal mics and a bit of level in the monitors, but that’s not really “full-service” and this IS a service industry. We have other things we can do…if we have the time. So create the time.

Make The Stage A Place You Want To Be On

Oh my. That stage is a mess, isn’t it? Cables are going everywhere from last night’s chaos, there’s gum stuck to various things, trash is strewn around, there’s a beverage glass jammed in a corner, and there’s a pile of wood fragments from that drummer whose hero is apparently Animal from “The Muppet Show.”

Guess whose responsibility it is to clean that up and make the stage look nice?

That’s right.

YOU have to have comfortable, happy musicians in order to do your job properly, and part of making people comfortable is presenting them with a working space that’s as nice as possible. So, get after it. You’ll be fine if you wash your hands afterwards.

Be Ready To Put Everything Through Some Part Of The Rig

Yes, it might be true that you technically don’t have to mic the amps or the drums to make the FOH mix work. However, just because you don’t need something in FOH doesn’t mean it won’t be wanted in monitor world. If you’ve got the inputs, plug things into them. Have the option available. The musicians will probably appreciate it, and that counts for a lot.

Also, make sure your gear is working during the course of setup. If a mic, cable, lighting instrument, loudspeaker, or whatever else is not cooperating, now is the time to find out. It’s easier to fix a problem before soundcheck rather than during, and much, much easier to fix a problem before the actual show is rolling.

A Tsunami Of Vocal

Vocals are often THE critical thing to get right in monitor world, so take the time to get a baseline sound that’s essentially pleasant, focused on the critical midrange instead of extreme low and high frequency “fru-fru,” and LOUD. You should take your basic cue from this chunk of Iggy Pop’s tour rider. (That’s where I got the “tsunami of vocal” bit.)

Now, yes, not everything will ultimately require “rock show” vocals in the monitors, but you have to be ready. You have to be prepared for situations where the ultimate volume isn’t that high, but the monitor-world loop gain is cranked. Start with the assumption that you need full-blown-rock-show level in the monitors, and make that work as well as you can. Make sure to kill your feedback problems as dead as they can possibly be killed. Test with all your vocal channels unmuted, because the total gain of the entire setup really does matter. A little bit of ringing is NOT acceptable. Do things as correctly as you know how.

If you’re particularly lucky, the musicians will be thoroughly impressed, and then ask you to turn things down. If you’re not particularly lucky, at least you’ll be prepared. (I have nothing against luck, and I acknowledge its ability to trump almost every other factor, but it’s not something you can plan on.)

Everything Else

For mics meant for other sources, you still have to have some idea of how they’ll work in monitor world. You do need to establish some kind of tuning to ward off their major problems regarding mixes for the deck. Your favorite instrument mic may have a tendency to ring at a certain frequency when you’re in a high-gain situation, so you need to get that under control. It’s possible that you’ll only have to take a look at the issue a few times – but you have to take that look.

Just as with vocals, the primary goal is to be able to supply the monitors with sound that’s basically nice to listen to, without a lot of “pre-emphasis” on any particular frequency range, and with plenty of level available. Run up the send level of an instrument mic and talk into it. Does it wound weird? Fix it.

Not On The Fly

Make sure your mixing console and/ or lighting system has “sane” presets applied. You want to be able to push things up in a hurry and have a result that is basically okay. Starting completely from scratch is a fun thing when you have rehearsal time and a single band to invest all your energy in, but that doesn’t happen so often in the small-venue world. (It’s especially rare when the venue signs your paycheck instead of an individual act or tour package.)

From a sonic perspective, if a mic is pointed at something and you push the fader up, the resulting sound should be a believable facsimile of that thing. From a lighting perspective, you should have several basic “looks” or “moods” that you can summon without having to think about it too much.

Don’t worry about your presets not being exactly right for everything. If they’re not helpful, you’ll recognize it and take steps to correct it (or learn to). If your preset works for the average case, it’s a good preset and will save you time. Dealing with something truly crazy has to be done on a case-by-case basis anyway, but the average stuff is what you’ll run across the most. That’s why it’s average.

Get The Band In The Room

I often say that loading the band in “is the job.” If the band isn’t in the room, and their gear isn’t in the room, then there isn’t going to be much of a show, right? So, get your hands dirty. Find some heavy stuff and move it. Not only does this help you actually get the show moving, it is often highly appreciated by the musicians. It’s a great way to actually show them that you’re all on the same team. It’s also a great way to prevent the band from getting fatigued before they’ve even played a note.

Also, to a certain extent, helping with the load in gives you a chance to really see the gear you’re going to be working with. If you see four toms for the drum kit, but you only have mics for three, you can make a note to get out another mic without having to be asked first. Did you run an XLR for the bass amp, but it doesn’t have an XLR direct out? Now you know, and you have a bit of time to get out a DI or set up a microphone.

But the main thing is to be helpful and facilitate the musicians being pleased.

Happy, comfortable musicians. Let that be your mantra.

Downbeat and Beyond

What’s Needed On Deck?

Your first priority is to get the stage sounding the way the musicians need it to sound. If they are comfortable and can play their best, then they will deliver the best show possible. Mixing FOH around what’s required for the musicians to deliver is a perfectly acceptable compromise. Forcing the sound on deck to conform to FOH in such a way that the actual performance is harmed? That is not an acceptable compromise.

This goes for lighting, too. If that super-moody light cue with the lasers prevents the players from seeing something they need to see, that just doesn’t work.

If the musicians are truly “in the zone” and fired up, that will translate to the audience. It will translate even if every production factor isn’t exactly where you might want it. You might not get to call your favorite light cues, or FOH might not be as clean and punchy as you might want, but the crowd is still very likely to be happy.

Vocals/ Melody, Then Everything Else

Anyone who tells you that drums and bass are the foundation of a mix is dead wrong. (There, I said it.) The foundation of the sound is the vocals. If there aren’t any vocals – either generally or just at some particular point – the foundation of the music passes to whatever carries the melodic theme.

I can prove my assertion about the vocals.

“Your head is humming and it won’t go – in case you don´t know

The piper’s calling you to join him

Dear lady can you hear the wind blow and did you know

Your stairway lies on the whispering wind?”

What song is that? That’s right! It’s “Stairway To Heaven” by Led Zeppelin. Amazing that you knew that without any music being played. Maybe it’s because you could understand the vocals?

I’m not saying that “Stairway” (or any other song) isn’t a total package. I’m not saying that the iconic guitar intro doesn’t matter. I’m not saying that the rhythm section is unimportant. The way the song builds to a thundering climax is a great bit of fun, and a major part of the song’s overall success.

What I AM saying is that if the vocals or key melodic elements – like a guitar solo – are lost while you try to dial up a crushing drum-n-bass tone, then you’ve got your priorities wrong.

Adjust For The Sake Of The Show

If you’re going to make a sonic change, that’s great. If you’re going to make a lighting change, that’s great.

But make sure you can easily justify that change in terms of serving the actual show. There’s a piece of advice that was given by Dave Rat which I particularly agree with:

Don’t fiddle.

That is, don’t make changes for the sake of making changes. Your existence at the audio or lighting console is justified by the need for an operator to be present and conscious; no further justification is required. If the EQ on the vocal channel is working, and you can’t supply a reason to change it other than “I have to change something,” then keep your paws off the EQ. If the light cue looks fine, and you’re worried that you should flash some PARs or twirl some movers because, you know, you’ve got all these buttons and knobs… Really. It’s okay. Leave it alone.

Of course, if the light cue looks okay, and changing to another cue will totally punctuate the transition to the song’s bridge, then PUNCH THEM BUTTONS, COWBOY!

Context matters.

I do support the idea of experiments. If you want to try something because you’re curious, then that’s a good thing. However, take the time to figure out how to do the experiment without calling a lot of attention to what you’re attempting. Be as subtle as you can. “Roll” things in and out instead of jumping around, if possible.

By extension, this also means that you don’t have to drive everything all the time. Let the music ebb and flow. The balance amongst all the parts doesn’t have to stay exactly the same all the time. Having that balance change just might be part of the ride. There’s no need to manage all the faders all the time. They will continue to exist even if you don’t touch them.

Breathe.

Try To Keep The Audience Happy

This one’s tricky, because you have to have a certain amount of confidence in your production decisions. You have to know when certain requests aren’t physically possible, or really aren’t in the best interests of the show at large.

Even so, do your best to be aware of the audience’s needs. If the crowd is running for the exits while holding their ears, then ask yourself if you’re being unnecessarily loud. If somebody asks for more bass/ less snare/ a different approach to the top end on the vocals/ whatever, then try to accommodate them if you can. This stuff is subjective, and if you can make one more person happy without wrecking the experience for everyone else, you might as well try it. The worst that can happen is that everybody else will hate the adjustment, and ask you to put things back to where they were.

This goes for lighting folks as well. Watch what happens when you call different cues, especially the ones that put light directly into the audience. If a bunch of people suddenly look unhappy, change to a different cue and don’t call the offender again.

Aftermath

Socialization

Once the show is over, you still need to keep the band happy. Try not to rush them out of the venue. Let them talk to the folks who came out, because that will help them build their audience. It’s also nice for players to just generally depressurize after all the excitement. Don’t run the post-show playback (if any) too loud. Giving everybody some time to unwind is just a courteous thing to do, if it’s feasible.

Load Out

The performers are probably rather tired after all the excitement, so the after-show is another great time to help with the moving of heavy objects. This further cements the idea that you and the band are on the same team, with an emphasis on building a good relationship for the next gig.

Further, this means that you can be on point to ensure that the gear is watched. Gear has a nasty tendency to get stolen in the post-show chaos, so keep an eye on things. If the load-out is a multi-trip affair, and it looks like gear might be left unattended, then stay where everybody else isn’t. You might just prevent something from “walking off.” Then, when somebody else returns, you can make another trip with a heavy object.

Setup Begins At Teardown

If you do nothing else, grab the grilles and pop-filter inserts off the vocal mics and wash them thoroughly. A nice, fresh, non-smelly vocal mic is much more hygienic, and also communicates (in a subtle way) that you care about the performers’ comfort.

If you know that someone else has to use the stage before you come back, then you have to clean up now. Get the cables wrapped and the trash picked up.

It’s ideal, of course, to get cleaned up even if you don’t strictly have to. Something might come up before the next show, meaning that you’ll have less time than you planned for. No matter what happens, leave the stage in a condition that you can manage even if you don’t have all the time you want for the next show’s prep.

Now, loop back to the top and do it all again…

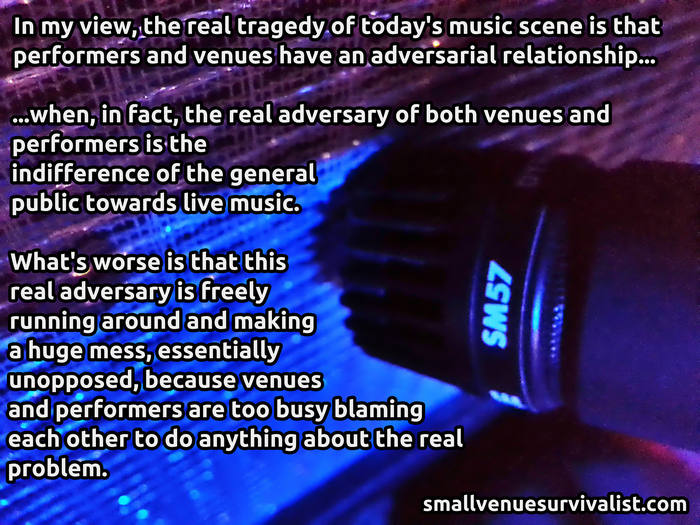

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.