I’m pretty sure that power – that is, energy delivered to loudspeaker drivers – is one of the most misunderstood topics in live-audio. It’s an area of the art that’s often presented in a simplified way for the sake of convenience. Convenience is hardly a bad thing, but simplifying a complex and mission-critical set of concepts can be troublesome. For one, misinformation (or just misinterpretation) starts to be viewed as fact. Going hand-in-hand with that is the phenomenon of folks who mean well, but make bad decisions. These bad decisions lead to the death of loudspeakers, over and under spending on amps and speakers, seemingly reckless system operation…the list goes on.

So, with all the potential problems that can be caused by the oversimplification of the topic “Powering Loudspeakers,” why does “reduction for the sake of convenience” continue to occur?

I think the answer to that is ironically simple: The proper powering of loudspeakers is, in truth, maddeningly complex. There are lots of “microfactors” involved that are quite simple, but when they all get stuck together…things get hairy. At some point, educators with limited time, equipment manufacturers with limited space in instruction manuals, and established pros with limited patience have to decide on what to gloss over. (I’ve done it myself. Certain parts of my article on clipping let some intricacies go without complete explanation.)

With that being the case, this article can’t possibly cover every little counter-intuitive detail. What it can do, however, is give you some idea of how many more particulars are actually out there, while also giving you some insight into a few of those particulars.

So, in no particular order…

Dirty Secret #1: Amp And Speaker Manufacturers Assume A Lot

You may have heard the phrase “Assume Nothing.” That saying does NOT apply to the people who build mass-produced loudspeakers and amplifiers. It doesn’t apply because it CAN NOT apply – otherwise, they’d never get anything built, or their instruction manuals would be gigantic.

Amplifier manufacturers, on their part, assume that you’re going to use their product with mostly “musical” signals. They also assume that you can put together a sane system with the “how to make this thing work” information they provide in their documentation. Further, they make suggestions about using amplifiers with continuous power ratings that are greater than the continuous power ratings of your speakers, because they assume that you’re not going to drive the amp up to its clip lights all the time.

Loudspeaker manufacturers also assume that you’re going to drive their boxes with music. They also ship products with the assumption that you’ll use the speaker in accordance with the instructions. They publish power ratings that are contingent on you being sane, especially with your system equalizers.

The upshot of it all is that the folks who make your gear also make VERY powerful assumptions about your ability to use their products within the design limits. They do this (and disclaim a lot of responsibility), because a ton of factors related to actual system use have traditionally been outside their control. Anytime you read an instruction manual – especially the specifications page – take care to remember that the numbers you see are simplifications and averages that reflect a mountain of assumptions.

Dirty Secret #2: Musical Signals Don’t Get You Your Continuous Power Rating

The reason that technical folks distinguish between signals like sine waves, pink noise, and “music” is because they have very different power densities. Sine waves, for instance, have a continuous level that’s 3 dB below their peak level. Pink noise often has to have an accompanying specification of “crest factor” (the ratio between the peak and average level), because different noise generators can give you different results. Some pink noise generators give you a signal with 6 dB between the peak and average levels. Others might give you 12 dB.

Music is all over the map.

Some music signals have peaks that are 20+ dB above the average power. Of course, in our current age of “compress and limit everything,” it’s common to see ratios that are much smaller. I myself use rather aggressive limiting, because I need to keep a pretty tight rein on how loud the PA system can go. Even so, my peak levels tend to be about 10 dB above the average level.

So if you’ve got an amp that’s rated for “x” continuous watts, and you drive the unit all the way to its undistorted peak, music is probably giving you x/10 watts…or less. In my case, the brickwall limit that I set is usually 10 dB below clip, which means that my actual continuous power is something like 5 watts per channel. This calculation is pretty consistent with what I think the speakers are actually doing, because they get about 96 dB @ 1 watt @ 1 meter. Five watts continuous would mean about 103 dB SPL per full-range box, and there are two full-range boxes in the PA, so that’s 106 dB total…yup, that seems about right.

Yeah, so, your system? If you’re driving it with actual music that isn’t insanely limited, you can go ahead and divide your amp’s continuous power rating by about 10. Don’t get overconfident, though, because you can still wreck your drivers. It’s all because…

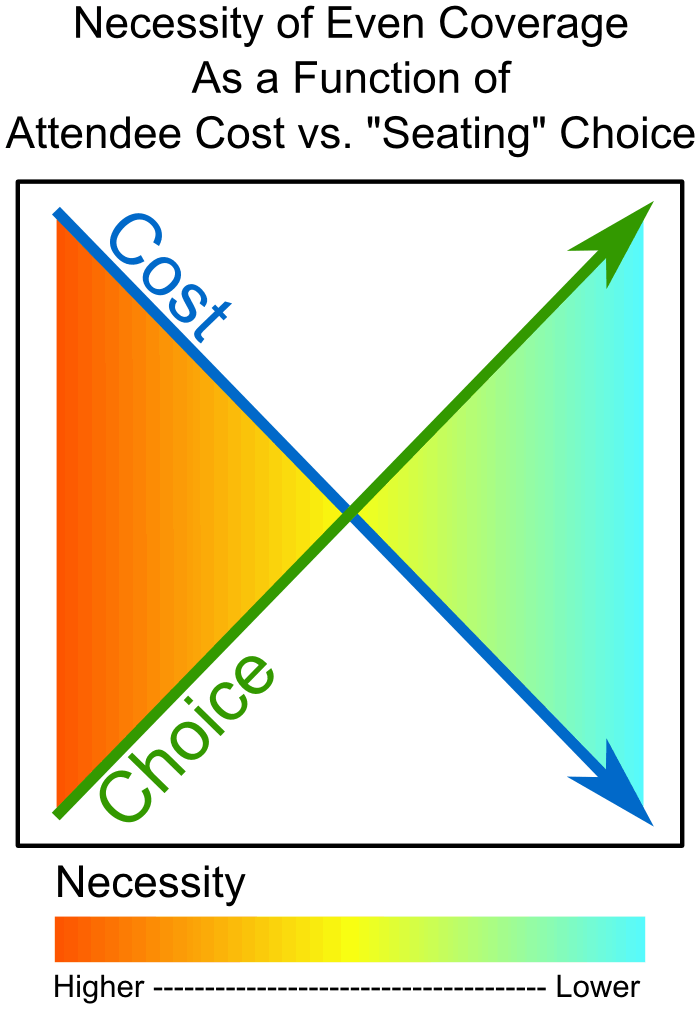

Dirty Secret #3: Power Isn’t Always Evenly Distributed

Remember that bit up there about manufacturers making assumptions? Think about this sentence: “They publish power ratings that are contingent on you being sane, especially with your system equalizers.”

Dirty secret #2 may have you feeling pretty safe. In fact, you may be thinking that secret #2 directly contravenes some of the things that I said about cooking your loudspeakers with an amp that’s too big.

Hold up there, chum!

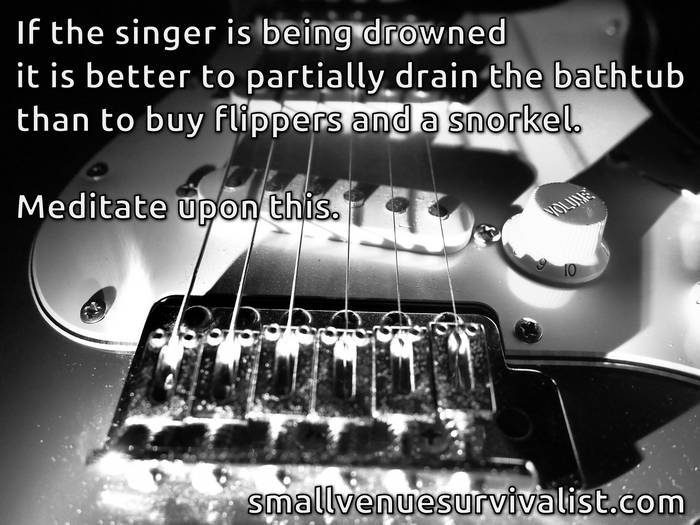

When a loudspeaker builder says that the system will handle, say, 500 watts, what they actually mean is: “This system will survive 500 watts of continuous input, as long as the input is distributed with roughly equal power per octave.” Not everything in the box will take 500 watts without dying. In particular, the HF driver may be rated for a tenth – or less – of what the total system is advertised to do. Now, if you combine that with a system operator who just loves to emphasize high-frequency material (“I love that top-end snap and sizzle, dude!”), you may just be delivering a LOT of juice to a rather fragile component…

…especially if the operator uses a huge amp, because they’re under the false impression that amp headroom = safety. A 1000 watt amplifier, combined with a tech who drives hard, scoops the mids, and has boxes with passive crossovers, is plenty capable of beating a 50-watt-rated HF driver into the ground.

On the flipside, a system without protective filtering on the low-frequency side can get killed in a similar way. Some audio-humans just HAVE to “gun”the low-frequency bands on their system EQ, because “boom and thump are what get the girls dancing, dude!” Well, that’s all fine and good, but most live-sound speakers that are reasonably affordable can’t handle deep bass at high power. Heck, the box that the drivers are in often acts as a filter for material that’s below about 40 Hz.

Of course, there may not be an electronic filter to keep 40 Hz and below out of the amplifier, or out of the LF driver. Thus, our system operator might just be dumping a huge amount of energy into a woofer without actually being able to hear it. The power doesn’t just disappear, of course, which means that “driver failure because of too much power at too low a frequency” might be just around the corner.

Dirty Secret #4: Accidents Aren’t Usually Musical Signals

Building on what I’ve said above, I should be clear that folks do get away with using overpowered amps (for a time) because of feeding them “music.” They end up keeping the peaks at a reasonable level, and so the continuous power stays in a safe place as well.

Then, something goes wrong.

Maybe some feedback gets really out of control. Maybe somebody drops a microphone. All of a sudden, you might have a high-frequency sine-wave with peaks – and continuous level – that’s far beyond what a horn driver can live with. In the blink of an eye, you might have a low-frequency peak that can rip a subwoofer cone.

Ouch.

Dirty Secret #5: Squeezing Every Drop Of Performance From Something Is For Either Amateurs Or Rich People

This secret connects pretty directly with #3 and #4. Lots of folks worry about getting every single dollar’s worth of output from a live-audio rig. It’s very understandable, and also very unhealthy. To extract every possible ounce of output from a loudspeaker system requires powerful, expensive amplifiers that have the capability to flat-out murder the speakers. For this reason, “performance enthusiasts” are either people who can’t afford to buy both more power AND more speakers, or they’re people who can afford to buy (and fix, and fix, and fix again) a lot of gear that’s run very hard.

The moral of the story is that your expectation needs to be that – in line with secret #3 – getting continuous output consistent with about 1/10th of a rig’s rated power is actually getting your money’s worth. If you don’t have enough acoustical output at that level, then you either need to upgrade to a system that gets louder with the same number of boxes, or you need to buy more loudspeakers and more amps to expand your system.

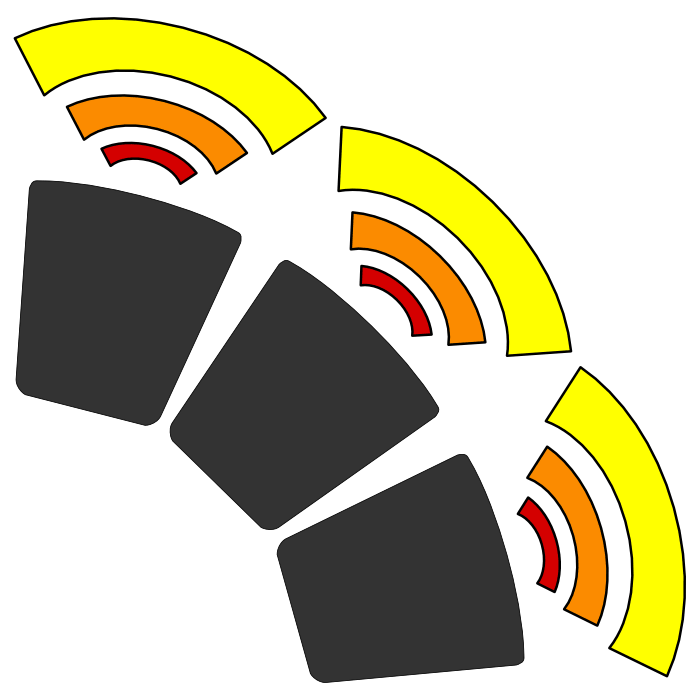

Dirty Secret #6: More Power Means More Than Just Buying More Amps

This follows along with secret #5. If you want more power, then you need more gear. That seems simple enough, but I’m convinced that linear PA growth is accompanied by geometric “support” growth.

What I mean by this is that getting ahold of a more powerful PA is more than just getting the amps and speakers together. More power means heavier and more expensive amp racks, or more (and more expensive because of quantity) amp racks. It may mean that you have to construct patch panels to keep everything organized. More PA power also means that you need more AC power “from the wall” in the venue. Past a certain point, you have to start thinking about an actual power distro system – and that can be a major project with huge pitfalls in and of itself. You need more space for storage. You need a bigger vehicle, if you’re going to transport it all.

Getting more power doesn’t just mean more of the “core” gear that creates and uses that power. It means more of everything that’s connected to that gear.

Dirty Secret #7: The Point Of Diminishing Returns Occurs Very Quickly. Immediately, In Fact.

The last secret is also, in some ways, the biggest bummer. Audio is a logarithmic affair, which means that the gains you get from spending more money and providing more power to a system begin decreasing as soon as you even get started. I’m dead serious.

For example, let’s say you’ve got a loudspeaker that averages about 95 dB SPL @ 1 watt @ 1 meter. You put one continuous watt – one measly watt – across the box, and stand roughly three feet away. That 95 dB SPL seems pretty good. Now, you go up to two watts. Did you get 95 dB more? Nope – that would mean that you could get “space shuttle takeoff” levels out of one loudspeaker. Not gonna happen.

So…did you get 20 dB more?

No.

10 dB?

Nope.

You doubled the power, and got three decibels more level out of the speaker. That’s just enough of a difference to definitively notice that things have gotten louder. If you want three more dB, you’ll have to double the power again. So far we’re only at four watts, but I think you can see just how fast the battle for more output starts to go against you. If your system is running at full tilt, and you want more output, you’re going to have to find a way to “double” the system – and even when you do, you’ll only get a little more out of it. If you want to get 10 times as loud, you need 10 times as much total PA.

The vast majority of a PA system’s output comes from the first watt going into each box. It’s a fact that’s in plain sight, but it (and its ramifications) often aren’t talked about very much.

That makes it one of the dirtiest secrets of all.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.

Want to use this image for something else? Great! Click it for the link to a high-res or resolution-independent version.