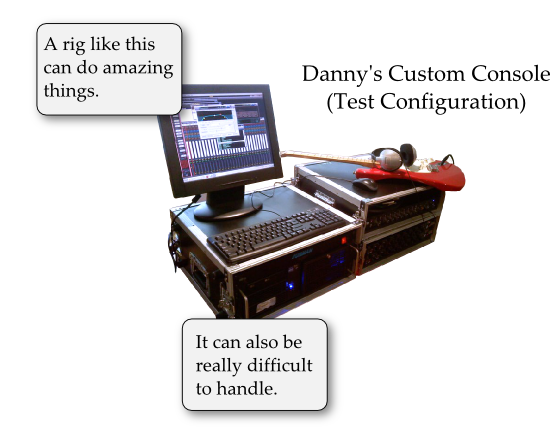

You don’t have to be in the big-leagues of production to get big-league functionality.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

So, I’ve already talked a bit about why “split monitoring” is a nifty idea. Independent signal paths for FOH and monitor world let you give the folks onstage what they want, while also giving FOH what you want – and without having to directly force either area’s decisions on the other.

…but, how to set this up?

Traditional split-monitor setups are usually accomplished with a (relatively) expensive onstage split. Individual mic lines are connected to the stagebox, which then “mults” the signal into at least two cable trunks. This can be as simple as bog-standard parallel wiring – like you can find in any “Y” cable – or it can be a more complex affair with isolation transformers.

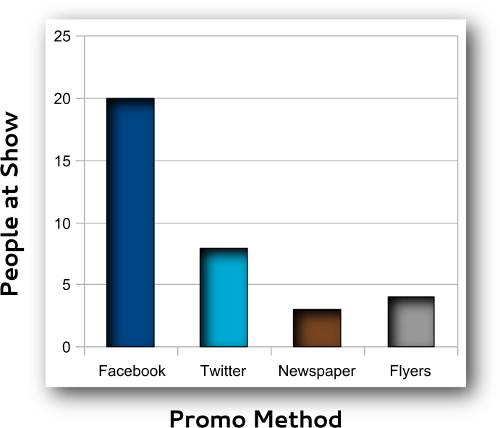

While you can definitely use a splitter snake or stagebox to accomplish the separation of FOH from monitor world, the expense, weight, and hassle may not really be worth it. Traditional splitters are usually built with the assumption that there will be separate operators for FOH and monitor world, and that these operators will also be physically separated. As a result, the cable trunks tend to be different lengths. Also, those same cables are made of a lot of expensive copper and jacketing material, and the stagebox internals can be even more spendy.

Now, if you actually need the functionality of a full-blown splitter snake, you should definitely invest in one. However, if you just want to get in on the advantages of a split monitor configuration, what you really need to shift your spending to console functionality and connectivity.

General Principles

Whether you implement a split monitor solution via analog or digital means, there are some universally applicable particulars to keep in mind:

- You need to have enough channels to handle all of your inputs twice, OR you need enough channels to handle the signals that are “critical for monitoring” twice. For instance, if you never put drums in the monitors, then being able to “double up” the drum channels isn’t necessary. On the other hand, only doubling certain channels can be more confusing, especially for mixes with lots of inputs.

- You actually DON’T need to worry about having enough pre-fader aux sends. In a split monitor configuration, post-fader monitor sends can actually be very helpful. Because you don’t have to worry about FOH fader moves changing the monitor mixes, you can run all your monitor sends post fader. This lets you use the monitor-channel fader itself as a precise global trim.

- If the performers need FX in the monitors, you need to have a way to return the FX to both the FOH and monitor signal paths.

- You need to be wiling to take the necessary time to get comfortable with running a split monitor setup. If you’ve never done it before, it can be easy to get lost; try your first run on a very simple gig, or even a rehearsal.

With all of that managed, you can think about specific implementations.

Analog

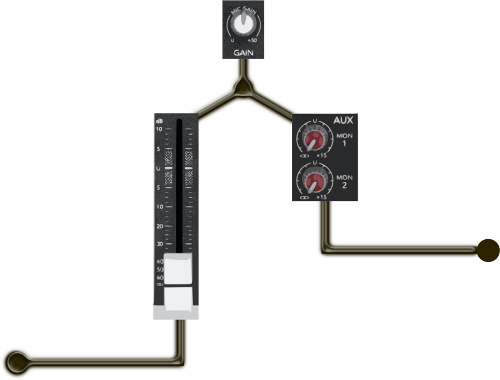

To create an affordable split monitor rig with an analog console (or multiple consoles), you will need to have a way to split the output of one mic pre to both the FOH and monitor channels. You can do this by “Y” cabling the output of external pres, but external mic preamps tend to be pretty spendy. A much less expensive choice is to use the internal pres on insert-equipped consoles. Ideally, one pre should be the “driver” for each source, and the other pre should be bypassed. Whether you pick the FOH or monitor channel pre is purely a matter of choice.

Your actual mic lines will need to be connected to the “driver” pre. On most insert-equipped consoles, you can plug a TS cable into the insert jack halfway. This causes the preamp signal to appear on the cable tip, while also allowing the signal to continue flowing down the original channel. The free end of the TS cable should also be connected to the insert on the counterpart channel, but it will need to be fully inside the jack. This connects the split signal to the electronics that are downstream of the preamp.

If you are working on a single console, you will need to be extra careful with your routing. You’ll need to take care not to drive your monitor sends from FOH channels, and on the flipside, you should usually disconnect your monitor channel faders from all outputs. (If all your monitor auxes are set as pre-fader, you can connect your monitor channel faders to a subgroup to get one more mix. This costs you your “global trim” fader functionality, of course. Decisions, decisions…)

Digital

Some digital consoles can allow you to create a “virtual” monitor mixer without any extra cables at all. If the digital patchbay functions let you assign one input to multiple channels, then all you have to worry about is the post-split routing. Not all digi consoles will let you do this, however. There are some digital mixers on the market that are meant to bring certain aspects of digital functionality to an essentially analog workflow, and these units will not allow you to do “strange” patching at the digital level.

As with the analog setup, if you’re using a single console you have to be careful to avoid using the monitor auxiliaries on the FOH channels. You also have to disconnect the monitor faders from all post-fade buses and subgroups – usually. Once again, if you don’t mind losing the fader-as-trim ability, setting all your monitor auxes to pre-fader and connecting the fader to a subgroup can give you one more mix.

Split-monitor setups can be powerful tools for audio rigs with a single operator. The configuration releases you from the compromises that can’t be avoided when you drive FOH and monitor land from a single channel. I definitely recommend trying split monitors if you’re excited about sound as its own discipline, and want to take your system’s functionality to the next level. Just take your time, and get used to the added complexity gradually.