My last article was primarily written to technicians. However, the issue of “only being able to get so much, in comparison to full-tilt boogie” has big implications for musicians playing live. Small venue, big venue, whatever venue, there’s an important reality that has to be faced:

There’s only so much that a PA system or monitor rig can add to the sound of an instrument or vocal.

Now, this certainly holds true in the aesthetic sense. There’s a practical limit to the amount of sweetening that can be applied to any particular sonic event. A drumkit (for example) that sounds truly horrific can’t really be “fixed in the mix,” especially if the tech doesn’t have hours to spend on making it sound like a different, much better drumkit. What really needs to happen is for that set of drums to sound decent, or even amazing, without any outside help. At that point, the PA’s job is to make those drums loud enough for the audience (if the drums aren’t already), and maybe add some “boom” and reverb – if appropriate.

There’s another sense of “what the sound system can add”, though, that’s much easier to quantify. This is the relatively simple reality of how much SPL (Sound Pressure Level) an audio rig can deliver for a given input from a given acoustical source. This “amount of level deliverable” is often less – even a LOT less – than what the rig can do on the spec sheet. (This can often be surprising, especially to musicians and techs who are still working on gaining practical experience with live performance.) The other side of the coin is how much overall level the PA should be adding to the show to have the result sound decent, and be at a comfortable for the audience.

How Much Should The PA Contribute?

When trying to get a handle on how much the FOH (Front Of House) PA should add to the show, there are a number of things to consider:

- How loud is the band, all by itself?

- What do you really want the PA to be doing? (Carrying the room? Just putting a bit more “thump” in the drums? Vocals only?)

- How much level will the audience and venue operators be happy with?

It can actually be helpful to work backwards through these points.

In small venues, the amount of tolerable level usually isn’t very high. Although some “pure music” rooms might work with 115+ dBC SPL continuous (decibels Sound Pressure Level, “slow” average), most places that cater to 200 patrons or less will probably see 110 dBC continuous as very, very loud. The problem is that, with a band and monitor rig that are REALLY cookin’, 110 dBC is very easy to achieve – and the PA isn’t even turned on yet!

In general, I recommend an upper limit of 105 dBC continuous for everything when working in a small venue. Band, monitor bleed, and FOH. Even that might be too much for some places, but it’s a start.

Once you’ve established how loud the whole show ought to be, you can begin figuring out what the PA’s contribution should entail. The handy rule of thumb here is that, for a given maximum volume, greater PA contribution requires you to keep a tighter rein on the stage volume.

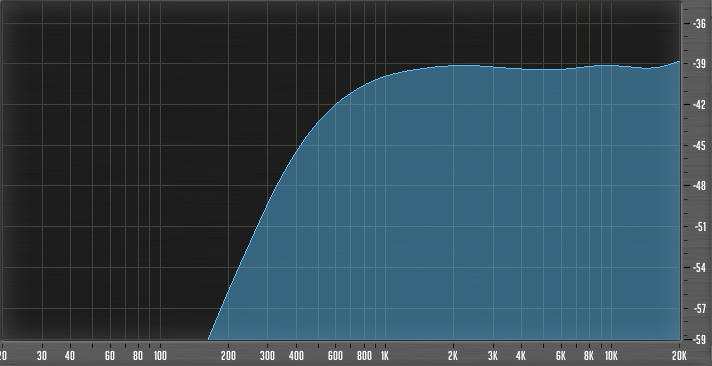

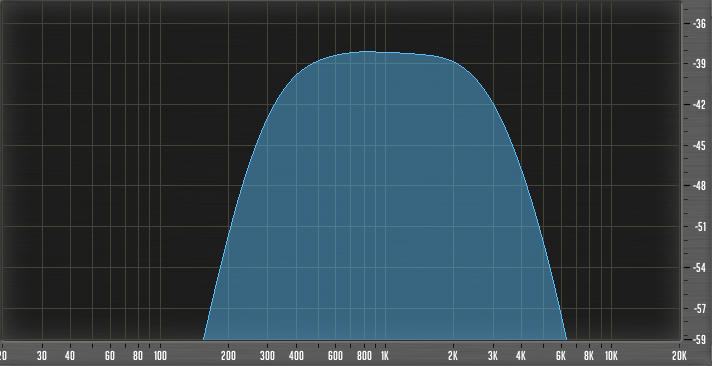

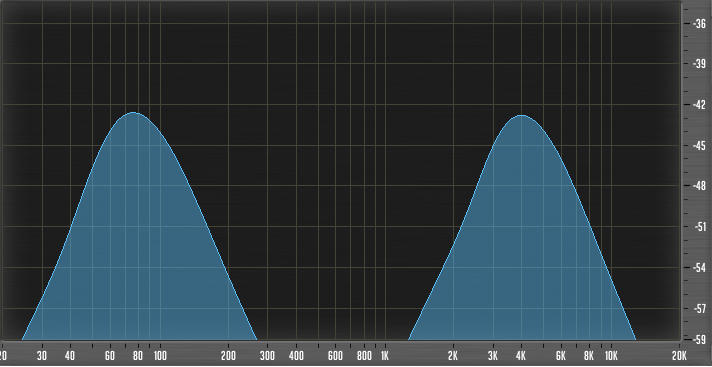

To help illustrate this point (and others), I’ve prepared some audio samples in OGG format. I’ve used a live recording of a drum kit from Fats Grill, along with a reverb processor, to roughly simulate three conditions:

Of course, this is an imperfect representation. Although most PA loudspeakers are designed to be somewhat directional, they still excite the reverberant field – they often don’t “dry out” the sound quite as much as these samples do.

Still, these clips give you an idea of what happens as more PA is applied. The overall level goes up, the PA sound starts to overcome the stage volume, and the transients get more defined. Putting more direct sound, with clean transient response into the audience is usually a good thing – but notice how much volume the PA had to add before the drumkit really “cleaned up.”

On a discussion forum, I believe that Mark from audiopile.net made a simple, profound, and very true statement with important implications: “Audio engineers don’t feel like they have control until they are 10 dB louder than everything else in the room.” With this guideline in mind, the issue crosses into the first point:

If you want the PA to really define how your band is heard by the audience, then the band’s stage volume should be about 10 dB below the PA. If the maximum volume for a small venue is about 105 dBC SPL continuous, this means that the band and monitor rig need to stay in the close vicinity of 94.5 dBC SPL continuous.

I’m not gonna lie – squishing a rock band into a box smaller than 95 – 100 dBC SPL is tricky. It can be done, but not everybody is willing to take on the challenge and make the decisions involved.

This is why, most of the time, small venue sound involves careful compromises. The PA is often used only to “fill spaces.” That is, the guitar amps might carry the room with only occasional reinforcement for solos, while the midrange and high-end from the drums is stage volume with a bit of “kick” from the subs. The vocals will be getting pretty much constant attention from the FOH rig, of course. In the end, the contribution from the FOH PA is minimal…or at least kept under tight control.

Proportionality Can Kick Your Butt

Beyond the issue of raw volume, though, is the conundrum of how much an audio reproduction system (be it an FOH PA or a monitor rig) can add to a given acoustical event on stage. This is where “sounding like a band without the PA” becomes really critical.

Here’s why.

For most audio rigs that are even half-decent, gain-before-feedback is at least as critical, if not more, than total output power. That is, a loudspeaker might be physically capable of creating earth-shattering SPL, but the squeals and howls of feedback will prevent you from actually getting there. Either the overall differentiation between the stage volume and the PA volume is too great, or the differentiation between on-stage sources is too great.

This is a little abstract, so here’s an object example.

Every so often, I’ll run into a group that has a proportionality problem. They’re not too loud for the room by any means – they might be an acoustic duo, for instance. The issue is that one person is vigorously strumming a big-body guitar, using a pick. Another person is playing a different guitar, with a much smaller body.

…and they’re playing fingerstyle.

Delicately.

Hoo, boy.

Depending on the players, that big guitar might already be a LOT louder than the small guitar – and then, the player of the big guitar decides that they want a pretty healthy amount of monitor level. No problem for the big guitar, especially if the instrument is free of resonance problems and includes a decent pickup. The small guitar? Well – it doesn’t have a pickup installed, so we had to mic it. We were only able to get “so” close, and the player’s not making a whole lot of level anyway.

The chances are that feedback issues will prevent even the most competent monitor operator from making that fingerstyle guitar compete with the big boy.

It’s not the absolute volume that’s the problem. It’s the proportionality. The massive level differential between the two instruments just can’t be dealt with in a live situation. In the studio, where feedback is basically non-existent, it’s another story. Here, though, getting through the set will be a struggle.

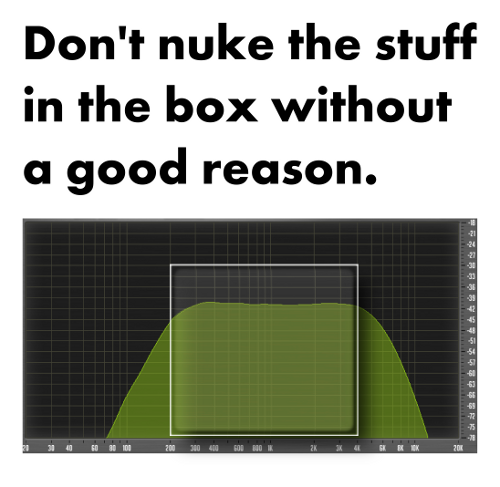

As a generality, I would propose the following guidelines for the feasibility of what a small-venue audio system can add to an onstage source’s volume – especially when talking about monitors on deck:

- +3 dB – Usually trivial.

- +6 dB – Usually very simple, if not entirely trivial. Depends on the situation.

- +10 dB – Average, may be challenging for sources that are resonant, or when using certain microphones.

- +20 dB – Difficult to impossible, can be done in certain cases with instruments that have well-isolated pickups and physical feedback reduction. May be possible with certain microphones in certain orientations relative to the monitors, or with common microphones and in-ear monitors. With line-inputs, noise may also be a problem.

- +30 dB – Generally impossible unless the source is completely feedback isolated. Noise from line inputs will probably be a big issue.

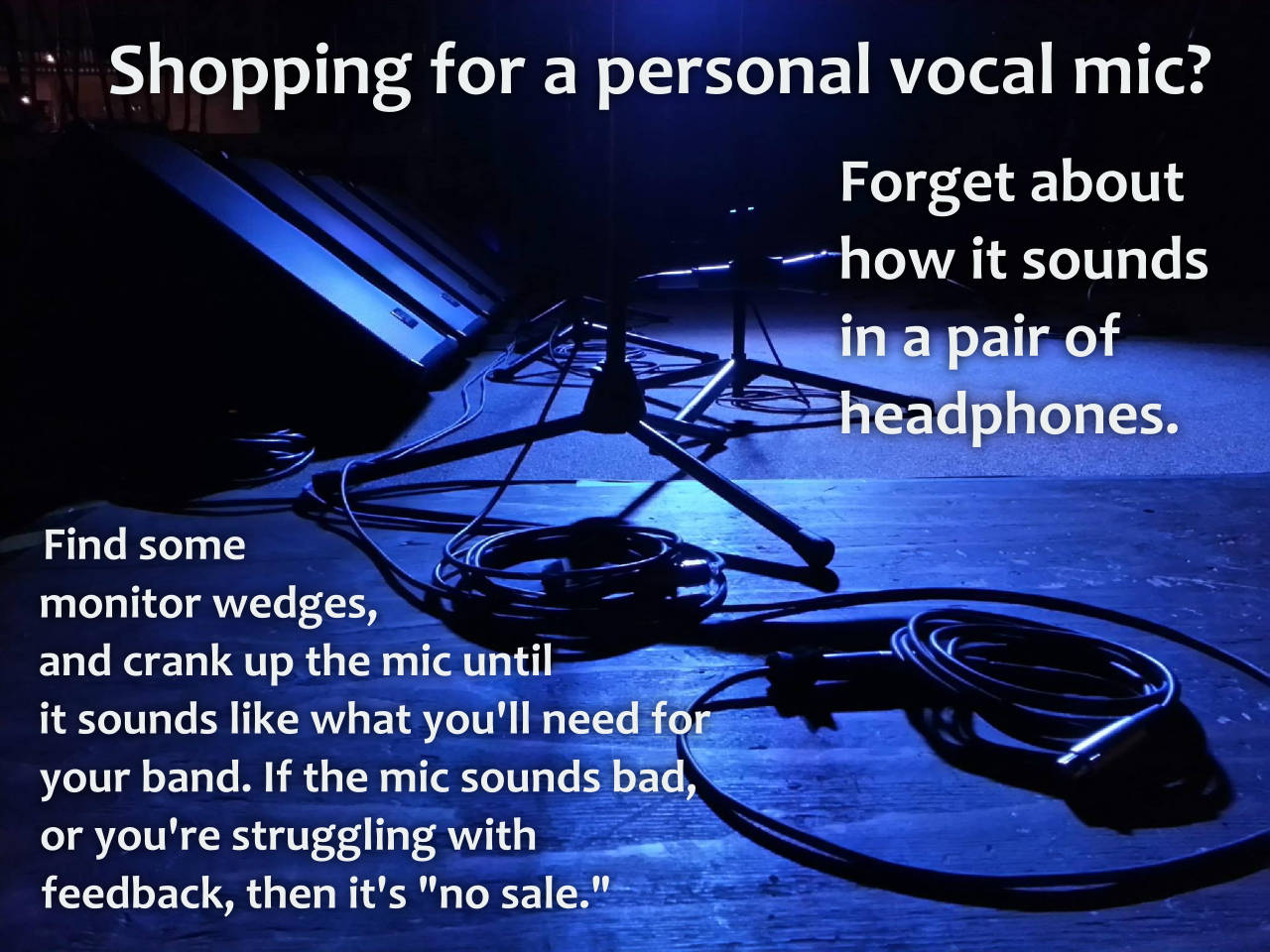

The way to get around these issues is to fix them before you arrive at the venue. If somebody is getting positively drowned during rehearsals, it’s simply not a safe assumption that a PA system (even a professionally operated one) will fix the issue. If everybody is clearly audible in rehearsal, on the other hand, then your proportionalities are either right on the money or “plenty close enough.”

This may sound a bit preachy, but I want to assure you that there are big benefits to “sounding like a band” before a PA system is added to the equation. If you’ve done the hard work of being balanced without outside help, then you have a much better shot at sounding killer with PA and monitor rigs that are only minimally adequate – or operated by a minimally competent audio human. Even better, when you get to work with great gear and great techs, they’ll be able to put their maximum effort towards presenting a flat-out amazing sonic experience for your fans. They’ll be able to do this because they won’t have to make the compromises necessary to fix big imbalances amongst instruments, or between the instruments and the vocals.

Bottom line? Being at the right volume, both in terms of absolute levels and relative balance, is a huge part of creating a brilliant stage show.