Getting your signal chain sorted out is key – especially when monitor world and FOH come together.

Please Remember:

The opinions expressed are mine only. These opinions do not necessarily reflect anybody else’s opinions. I do not own, operate, manage, or represent any band, venue, or company that I talk about, unless explicitly noted.

Sometimes, you have to do things that “break the rules.”

Audio-humans internalize a lot of pointers as they learn their craft, and those tactics are often in place for very good reasons. When a given way of making things happen has survived for decades, it’s usually because it’s either a really good idea, or we just haven’t found a way around it yet. The problem that arises, though, is that a lot of techs don’t know the “deep roots” of why certain signal flows are as they are.

For instance, just about everybody knows that a gate should – 99% of the time – be placed pre-compression. Not everybody can verbalize the “why” of that rule, though. The “deep root” of the rule is that dynamic range expansion (gating) works more effectively as the dynamic range of an input signal increases. The less of a level difference that you have between the material you want gated out and the material you want to keep, the less able you are to cause the gate to discriminate between the two. Compressing a signal at some point that’s pre-gate is just working against yourself, because compression is dynamic range reduction.

But I digress.

The point of this article isn’t to get into every kind of signal flow arrangement. The idea here is to relate an anecdote that shows why I had to “break some rules” recently. It was all in the name of getting FOH (Front Of House) and monitor world to play nicely.

FX Out Front and On Deck

As I was soundchecking a band, one of the players expressed a request to have reverb on his instrument. He also specifically requested that the reverb be routed to the monitors.

Here’s where the trouble can start.

See, “everybody knows” that reverbs are fed from post-fader sends. Most of the time, this is the right thing to do. You use the send to create a reverb proportionality, and if you end up pushing the channel level around, the proportionality stays the same. If the fader goes up 6 dB, the reverb level goes up 6 dB – the wet/ dry mix remains as it was set. That’s a good thing.

Except when it isn’t.

The problem in the “Curious Case of a Reverb That’s Going to FOH and Monitor World” is that you DON’T want the reverb level to track with level changes out front. If it does, then the wet/ dry blend on deck can go all over the place during the show. This is especially true in small venues, where a instrument may be completely “out” until a solo, at which point you drive the level up into audible territory. That could mean an effective dynamic range of 80 db or more. Possibly a lot more.

Obviously, appearing and disappearing reverb isn’t what the gents on stage are after. As a result, the “post-fader sends to FX” rule has to go out the window, because it’s no longer appropriate. Instead, the reverb has to be run from a pre-fader send. As long as you don’t fiddle with your preamp gain, the reverb level will be unaffected by what you’re doing out front.

Or will it?

The other thing you have to be aware of is where that pre-fader send lives in relation to your channel EQ. If you have something bizarre going on with the channel EQ for FOH (and you very well might), and that pre-fader send takes a split AFTER the EQ, your reverb may sound awfully strange.

What To Do, What To Do?

The first thing that you have to do is prioritize. In most cases, making a consistent blend “easy” for monitor world should come before making FOH easy. (There’s probably a whole article to be written about this, but the short version is that you can often hear, and act on, issues in FOH faster than issues on deck.)

The next thing to do is to figure out what you need for that prioritization to be fulfilled. In this case, I needed reverb that was driven from a pre-fader, pre-EQ signal. I also needed the “wet” audio from the reverb to be independently routable to FOH and the monitor wedges. Making this happen for me is no problem, because I run a console with insanely flexible routing. I can actually use “subchannels” within channels to pass audio “around” processors, and any channel can send to or receive from any other channel. I also have the built-in option to run sends pre or post any channel processing.

But, what if you don’t have all that?

Heck, what if you don’t have completely separate sets of channels for FOH and monitor land?

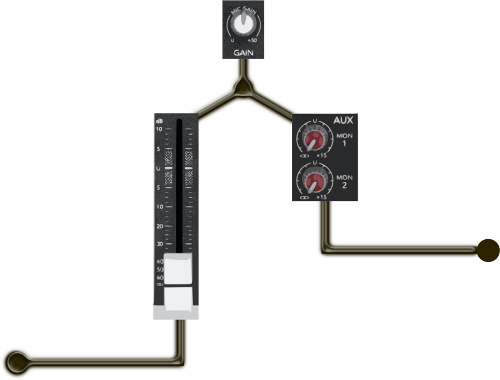

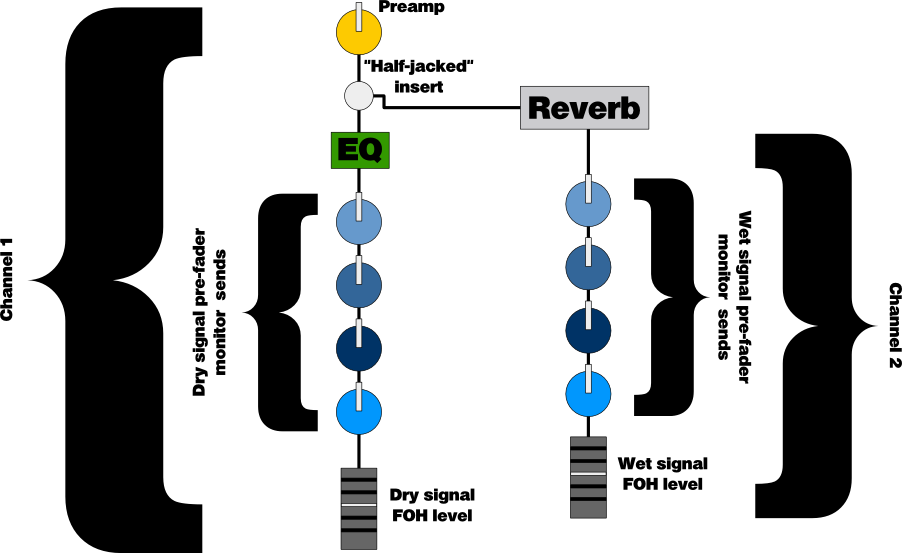

You can still make this happen. Take a look:

The “half-jacked” insert lets you mult (split) the original signal over to the reverb. At the same time, the signal continues to flow through the FOH channel and its monitor sends. You can then take the reverb processor’s output, put that in a different channel, and use the pre-fader sends to get reverb to monitor world. The reverb channel’s fader output can then be blended into FOH as necessary.

With this kind of setup, you can go hog-wild with your FOH levels, and monitor world won’t be directly affected. There are other ways of accomplishing this, of course, but this setup is one of the simpler ones.

Yes, this is a bit more complicated than what you might think of “off the cuff,” but it lets you have what you need out front without compromising what the folks on deck can have for themselves. I think it’s worth doing if you have the channels, and it’s not that hard to adapt to your own needs…

…you just have to remember that “the order matters.”